How Did Reagan Impact the Cold War Ib History Review

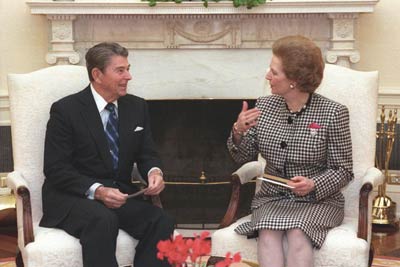

Margaret Thatcher was more willing to accept the premise of SDI becuase she had a "healthy respect" for United states applied science. (credit: Ronald Reagan Library)

SDI and the end of the Common cold State of war

The contend over the part that Ronald Reagan's Strategic Defense force Initiative (SDI) played in ending the Cold War shows no sign of cooling off. Indeed there is every indication that it will merely keep and on, like the debates over how World State of war One started in 1914 or the ones in France over the "positive role of colonialism". John O'Sullivan's new book, The President, the Pope, and the Prime Government minister, brings an interesting British perspective to the statement. Every bit a announcer, editor, and one-time banana to Mrs. Thatcher, he had a forepart row seat for the Uk'southward part of the cracking "Star Wars" battles of the 1980s.

In Britain, as elsewhere, Reagan'southward March 1983 speech launching SDI was met with incredulity and not a little disdain. Ted Kennedy notoriously dubbed it "Star Wars", and few experts outside a small circle of defence enthusiasts understood the profound implications of the President'due south question, "Would information technology not be amend to salvage lives rather than avenge them?" The old, unpalatable choices of Armageddon or artillery command suddenly seemed to be out of date.

In the early 1980s the big political conflict in Europe was over the installation of U.s. cruise and Pershing missiles to counter the Soviet SS-20s. The anti-nuclear movement went all out to try and derail the NATO deployment. As O'Sullivan points out the Soviet "'Peace' strategy had proved to be a bright one. It cloaked an important Soviet strategic interest in a multicolored garment woven from environmentalism, religion, pacifism, riot, and old fashioned radicalism. At its peak it could bring millions into the streets overnight. It reshaped the political culture of the left and thus of countries where the left was culturally dominant. It was and so successful that information technology was imitated wholesale past the American left in the 'nuclear freeze' motion. It could do anything except win elections."

Equally O'Sullivan puts information technology, "Equally a scientist with a healthy respect for U.Southward. technology, she [Thatcher] never shared the outright scorn for SDI expressed by about European governments and military experts."

Thus in Europe, and especially in U.k., SDI was not seen as all that important compared to the reality of the Euromissiles scheduled for deployment in the late fall of 1983. Only a few defense experts realized what the existent stakes were and they had little to practice with the much-ballyhooed research contracts. From the British government's point of view the implications were ominous. The opposition Labour Party was committed to the idea of unilateral nuclear disarmament and they lost the 1983 election in part due to that fact. Thatcher had expended much political majuscule convincing her cabinet and the voters to renew Britain'southward national nuclear deterrent force by replacing the old Polaris missile submarines with new Trident ones.

All of a sudden, her close friend and ally, the President of the Usa, appear he was embarking on a programme that aimed to make all such weapons "impotent and obsolete." Similar about all European leaders, she simply did not know what to make of it, only unlike most of them she knew Reagan well enough to know that he had thought the thought through. Every bit O'Sullivan puts it, "As a scientist with a healthy respect for U.South. technology, she never shared the outright scorn for SDI expressed past most European governments and military machine experts." One might add that Uk's experience using American weapons against the Argentines in the 1982 Falklands war probably likewise had an impact.

While in private she was worried about the possibility that SDI might "decouple" the Us from the defense force of Europe, she had the good sense to keep her doubts to herself. Europeans who insisted that Soviet missiles be given a free ride towards their US targets could scarcely then turn around and insist that the Us put tens of thousands of American lives at stake to finish the Cherry-red Regular army from having a free ride across Western Europe to the Aqueduct and across. What she wanted was a missile defense organization that would enhance deterrence. One that would create such uncertainty in the minds of the Moscow leadership that their massive investment in offensive nuclear systems would exist effectively neutralized.

This was not what her great friend Ronald Reagan had in mind. Throughout the late 1970s his radio commentaries had warned against Soviet nuclear superiority and against the bad deals that the Nixon and Carter assistants had negotiated during the SALT process. In 1978 he quoted sometime Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird, "The evidence is incontrovertible that the Soviet Marriage has repeatedly, flagrantly and indeed contemptuously violated the treaties to which nosotros accept adhered." That aforementioned year he evoked the possibility of a nuclear war where "…they [the Soviets] lose 5% of their population and we lost 50% or more."

He must have seen that being stuck in a competition to build more missiles while supposedly trying to achieve arms control deals that would restrain this process, was a fools game. One that the USSR was bound to win. Something had to change, in the brusk term he knew he had to build upwards US nuclear forces and to talk with the Soviets at the same time, only neither of these choices satisfied him.

To imagine, as some of his detractors do, that information technology was his 1979 visit to NORAD in Colorado Springs that showed him that America lacked whatever sort of missile defense is typical of their attitude towards him, summed up in Clark Clifford's famous label "amiable dunce". As O'Sullivan makes articulate, "What surprised and upset Reagan at NORAD was the disparity between the excellence of the engineering science and the modesty of its purpose. If we could rail missiles from their launch he asked reasonably, could we not develop a means of halting them?" While O'Sullivan does not mention information technology, what Reagan had seen was the Defense Support Program (DSP) satellites in functioning. Their ability to track the estrus signature of a missile launch hinted at what might be technically possible.

Reagan did not totally reject arms control: his aim was to enter into the talks from a position of force. As he saw it, recent administrations had negotiated from weakness, due both to Vietnam and to the constant pressure from Congressional doves to cut the defense budget. More importantly he always thought that the SALT talks were only not ambitious enough. He wanted to eliminate nuclear weapons entirely, but he also wanted to win the Cold War.

"What surprised and upset Reagan at NORAD was the disparity between the excellence of the technology and the modesty of its purpose. If we could rail missiles from their launch he asked reasonably, could we not develop a ways of halting them?"

As O'Sullivan reminds us, Reagan had a very simple strategic approach to the Cold State of war "Nosotros win, they lose." Unlike most Sovietologists and other bookish experts, the old player understood that Communism was a failing economical system. He did grasp of central bulletin of the Communist bloc dissidents, as well every bit dozens of refugees, and defectors. The Soviet economy was a nightmare that was only really efficient at producing weapons and creating raw armed services strength.

Meanwhile he knew that the US economic system was producing new technologies at a rate the Soviets could never promise to match. While it might be a flake much to say, as O'Sullivan does, that Reagan and Thatcher'south complimentary marketplace policies "midwifed" the data revolution, they certainly gave it an almighty shove in the right management.

There is of class a lot more to this book than just the SDI story. The sections on Pope John Paul 2 are heart opening to a non-Catholic like myself. Poland's struggle for freedom was in its own style simply every bit important as SDI. Elsewhere O'Sullivan sums up in a few brusque pages why Reagan and Thatcher's economic policies were then different, although guided by essentially the same philosophy.

Its useful to remember that Reagan'southward concluding years in office were seen by many, including many conservatives, as a failure, due to Islamic republic of iran-Contra and his being overshadowed past Gorbachev. In the low-cal of history, though, we know that his simple goal was achieved: "We won, they lost."

Habitation

Source: https://thespacereview.com/article/742/1

0 Response to "How Did Reagan Impact the Cold War Ib History Review"

Post a Comment